Dr. Vu Thanh Tu Anh, senior lecturer at the Fulbright School of Public Policy and Management, Fulbright University Vietnam, presented a compelling and well-researched argument at the national scientific conference hosted by the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences. Below is a summary.

Vietnam at a crossroads

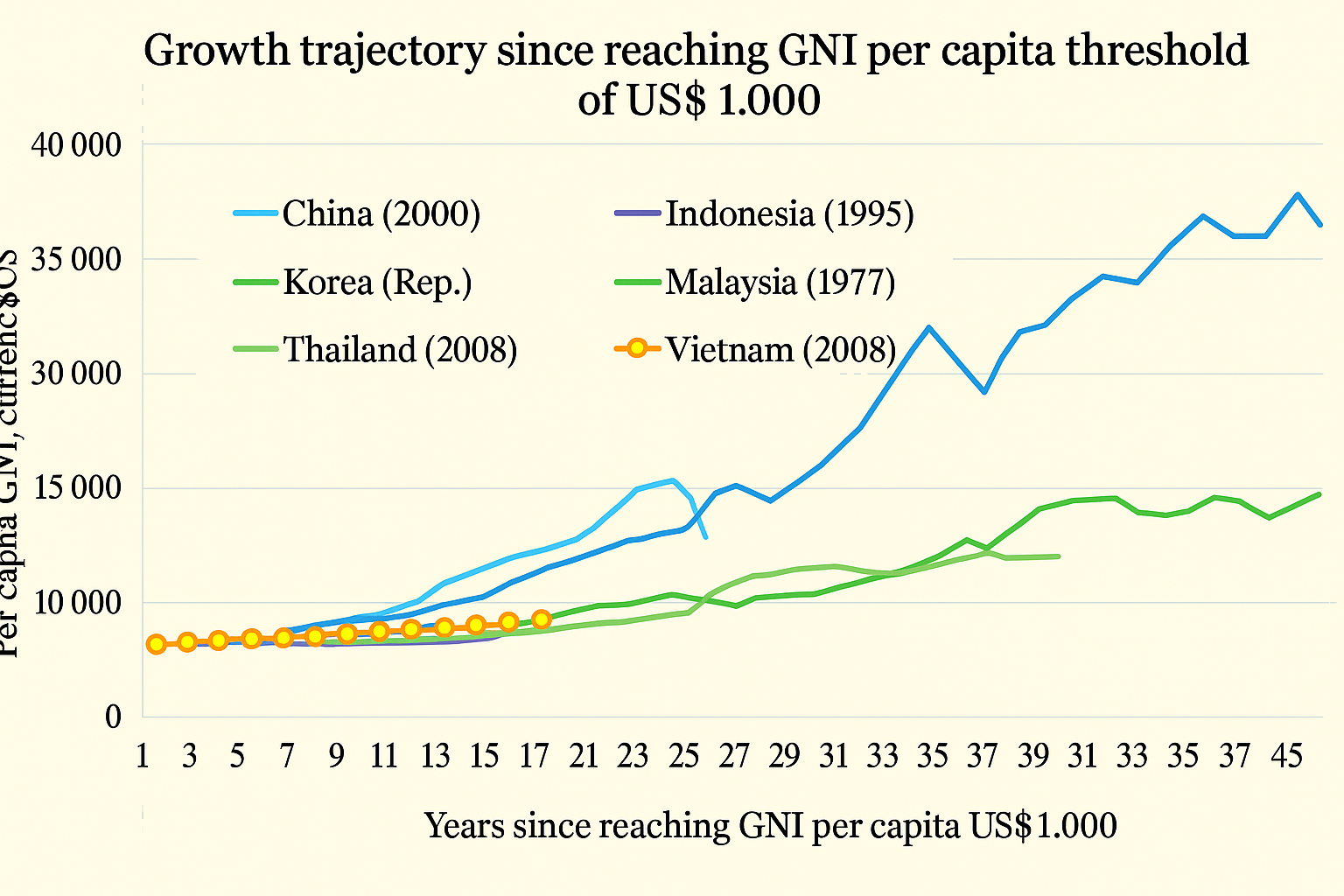

Geographically, Vietnam is positioned between Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia. Economically, since surpassing a per capita income of $1,000, Vietnam’s growth trajectory has outpaced Southeast Asian peers like Malaysia and Thailand but remains behind Northeast Asian giants such as South Korea and China.

As Vietnam’s gross national income per capita has now exceeded $4,000 (Atlas method), the nation aspires to reach high-income status by 2045. What growth path could lead there?

Three scenarios of economic growth

In the first scenario, with an average annual growth of just over 6% - the pace of recent years - Vietnam would reach a per capita income of around $16,000 by 2045.

In the second, more ambitious scenario of 7% growth, income would rise to approximately $19,700, close to the threshold of high-income status.

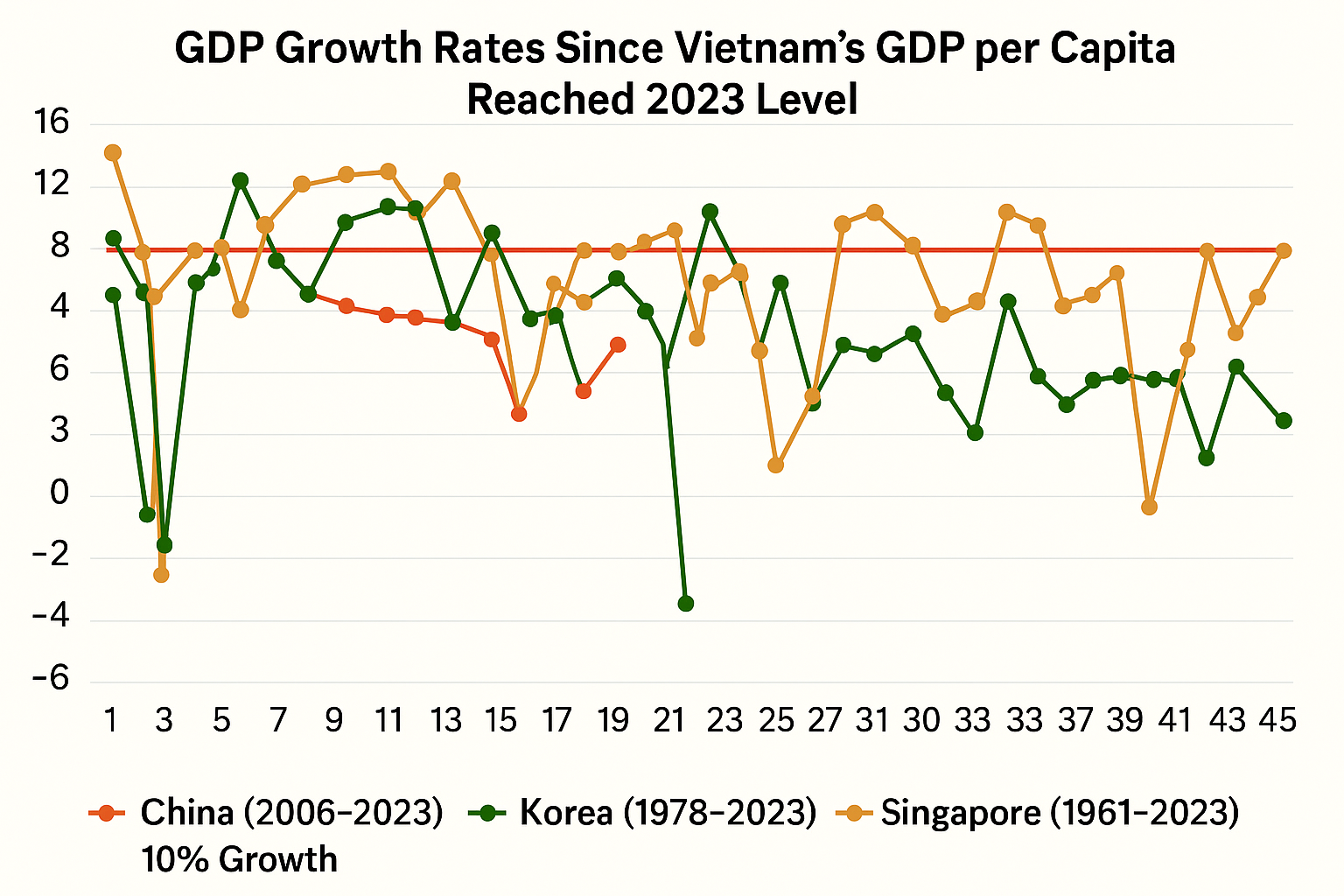

But only with 10% annual growth would Vietnam surpass $33,000 in income by 2045 - comparable to South Korea in 2019 - entering the group of developed Northeast Asian economies.

However, even sustaining 7% growth is challenging, requiring a total factor productivity (TFP) increase of 4% - already an extraordinary feat. A 9% GDP growth would need a TFP growth of 5.6%, a figure rarely achieved even in successful Northeast Asian economies.

Another challenge is demographic: Vietnam is entering an aging phase. Labor force growth has declined from 2% to 0.5%, soon turning negative. To compensate, productivity must increase dramatically - this is Vietnam’s primary challenge.

Historically, nations with rising incomes face slowing growth. In Asia, only Singapore and South Korea maintained a 10% per capita GDP growth after crossing the $4,000 threshold.

The Northeast vs. Southeast Asian model

Countries in Northeast Asia succeeded through deep structural shifts: industrialization, urbanization, economic diversification, strong institutions, competent governance, human capital development, and high-value global integration.

Southeast Asian nations (excluding Singapore) like Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia experienced more limited structural transformation.

Unless Vietnam successfully transforms its economic structure, achieving 10% growth over 20 years is out of reach.

Three pillars for sustainable transformation

1. Inclusive institutions

Political centralization must be balanced with democratic participation, rule of law, anti-corruption, and power equilibrium between state and society.

2. Market economy with private sector at the core

Vietnam must embrace a private-sector-driven growth model, informed by comparative advantage and latecomer advantages. Resolution 68 recently emphasized the private sector as the centerpiece of national development.

Vietnam, however, faces a different context than Japan, South Korea, or Taiwan. With deeper global integration, extensive international commitments, and fierce competition from a dominant China, Vietnam must chart its own industrial policy path.

3. Developmental state

Vietnam needs a state capable of enabling transformation - not obstructing it. This requires re-centering the state’s role in policy design, execution, and enforcement.

Revitalizing the nation requires competent, visionary civil servants with integrity and national pride - akin to the technocratic traditions of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Although Vietnam values talent, it has yet to match these Northeast Asian standards. The state apparatus must become the backbone of transformation.

Without it, Vietnam may continue to announce ambitious restructuring programs, but with no effective implementation mechanism.

Boosting state capacity and democratic space

Three critical levels of state capacity:

1. Political legitimacy and high-level commitment – which Vietnam currently has.

2. Policy-making capability – still lacking in coherence, coordination, and execution.

3. Administrative capacity – facing a mismatch between ambitious mandates and limited machinery.

Consider South Korea’s pathway: the country built a capable state and expanded citizen participation after GDP per capita reached $8,000–$10,000. Taiwan followed a similar trajectory.

Vietnam, if it maintains current growth, may approach this democratic inflection point within a decade. But if state capacity is not enhanced, the moment may be missed.

Vietnam’s growth curve: At a pivotal moment

Vietnam currently appears to follow the Northeast Asian path, steadily increasing state capability. However, it has yet to reach the point of democratic expansion - necessary to become a modern state.

Six strategic insights for the future

1. Strengthen state capacity to manage a complex domestic and global economy.

2. Foster pride among civil servants for contributing to national development - emulating the ethos Peter Evans described in his work on South Korea.

3. Promote adaptive and flexible governance - a crucial trait in a rapidly changing world.

4. Empower the private sector as the main engine of growth.

5. Ensure alignment between institutional capacity and reform speed - to prevent breakdowns from overly ambitious changes.

6. Balance growth with risk management - much like a fast car needs good brakes, growth must be tempered with geopolitical, macroeconomic, and institutional safeguards.

Ultimately, development must improve lives and bring happiness. This requires a fine balance between state authority, freedom, democracy, and societal dynamism - an insight powerfully argued by Acemoglu and Robinson, Nobel Laureates in Economics 2024, in “The Narrow Corridor.”

Tu Giang - Lan Anh