In celebration of the 50th anniversary of Vietnam’s reunification, VietNamNet presents the series "April 30 - A New Era," featuring reflections and memories from military experts, historians, and witnesses of history, highlighting lessons of unity, international solidarity, resilience, and the enduring spirit of the Vietnamese people.

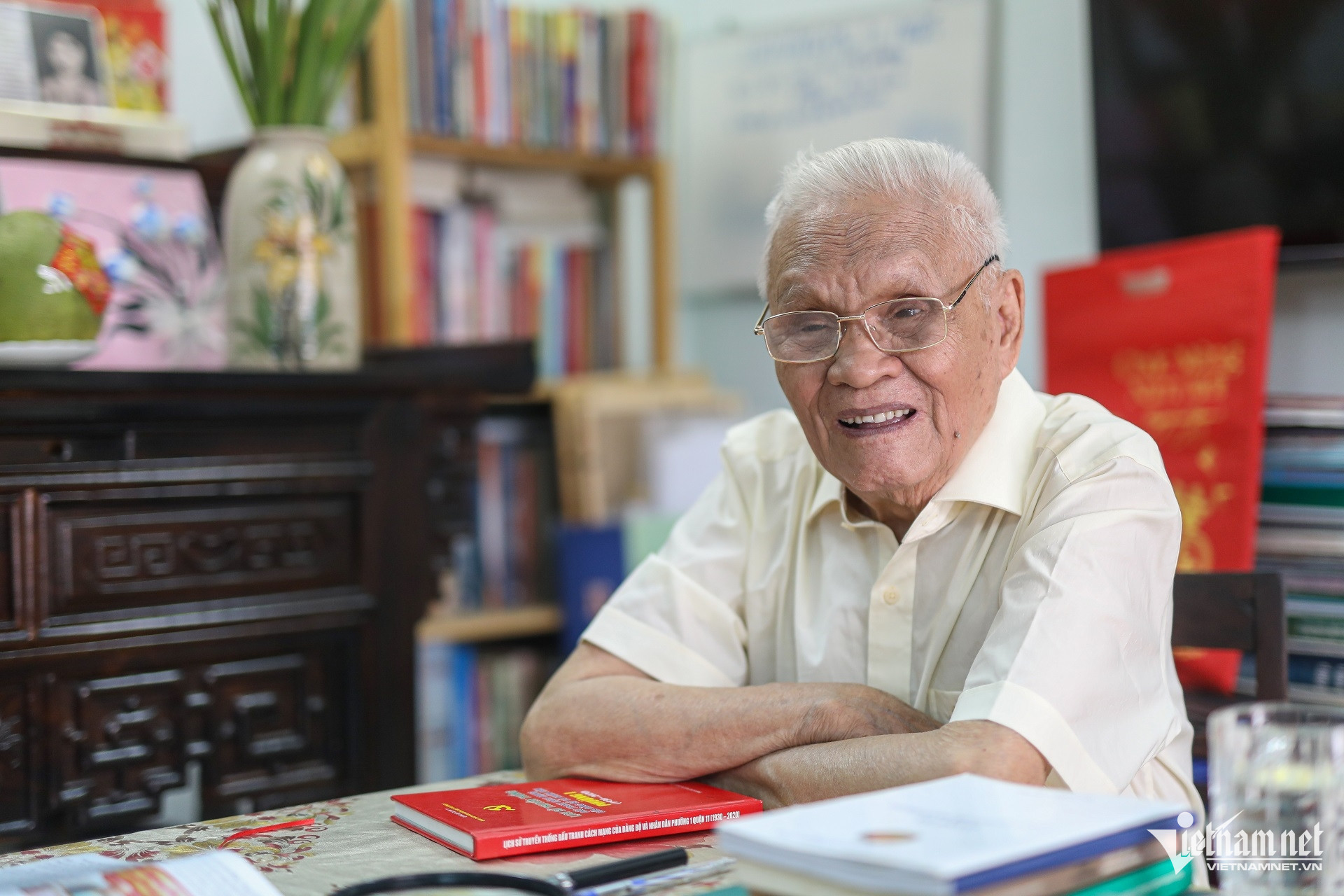

Huynh Van Cang, also known as Tu Cang, born in 1928, resides on the ground floor of a modest house at the entrance of the alley. A retired cadre, he once served as secretary to Vo Van Kiet, then Secretary of the Saigon - Gia Dinh Regional Party Committee (and later Prime Minister). He also held roles as Chairman of District 11 People's Committee and Director of the Department of Labor, War Invalids and Social Affairs of Ho Chi Minh City.

Mr. Cang feels fortunate to have been in Saigon on the historic day of April 30, 1975.

In November 1965, after a decade in the North, Tu Cang returned to the South, working for the Propaganda Department of the Saigon - Gia Dinh region’s rural sector.

In 1967, he was reassigned as secretary to Vo Van Kiet. A year later, when Kiet moved to the Mekong Delta, Cang continued working as secretary for other regional leaders.

In early March 1975, during the Central Highlands campaign, Cang, then serving at the office of Mai Chi Tho (Secretary of the Saigon - Gia Dinh Regional Party Committee), was ordered into Saigon to prepare for the uprising. Assigned to oversee the Phu Tho racecourse and Lu Gia area, he quickly mobilized.

"Mai Chi Tho told me to help the people rise and welcome the liberation forces," Cang recalled. "When he gave the order, I immediately called the liaison officer and left within an hour. Tho laughed and asked, 'Why the rush?' I said, 'Afraid you might change your mind!'"

By then, the anti-American movement among the people of Saigon was strong, especially after the Tet Offensive.

Within the city, Cang built networks, encouraging patriotic teachers and customs officials - groups unlikely to be searched - to shelter revolutionary cadres preparing for the takeover.

At the Phu Tho racecourse, a stronghold of Republic of Vietnam forces, Cang realized danger loomed: "If our tanks advanced while the enemy soldiers remained armed, a firefight could erupt," he said.

He quickly organized a broadcast urging soldiers to lay down arms, remove their uniforms, and peacefully return home.

"Within 30 minutes, the soldiers had surrendered their weapons and left peacefully."

Notably, it was the only unit in Saigon at that time to successfully use public broadcasting to secure a mass surrender.

The next morning, Cang was invited by a priest to speak to the congregation at a church on Nguyen Thi Nho Street, Tan Binh District.

"I spoke from the heart, telling them that victory belonged to the entire Vietnamese people, whether religious or not, and that no one willingly fought against the revolution. The church courtyard was packed, and after the talk, the priest shook my hand and thanked the revolution for liberating Saigon peacefully."

A special altar for "five eternal inspirations"

In his humble home, Cang’s most honored spot is a small altar adorned daily with fresh flowers and fruit. It holds the portraits of five figures he most deeply reveres: President Ho Chi Minh at the center, flanked by General Vo Nguyen Giap and Prime Minister Vo Van Kiet, and on the edges, Doan Cong Chanh (alias Sau Khiem) and martyr Vo Thi Sau.

"These are the people who have lived in my heart," Cang shared. "Without Uncle Ho and General Giap, we wouldn’t have the nation we have today. Prime Minister Vo Van Kiet exemplified decisiveness and clarity, while Vo Thi Sau’s courage at such a young age deeply moves me."

Cang also fondly recalls Sau Khiem, whom he describes as "principled and modest." Khiem’s deep sense of discipline and humility left an indelible mark on him.

He recounted how Khiem once refused to eat bananas bought at an inflated price, insisting on returning them to avoid disrupting the market - a reflection of his unwavering ethics.

At Cu Chi, Khiem suffered from chemical exposure but refused extra allowances for his condition, saying, "My salary is enough."

Two lifelong prides

Born in the heroic land of Cu Chi, Huynh Van Cang takes pride in two key achievements.

"First, I am proud that I devoted my heart and life to the Party and to Uncle Ho’s ideals, living meaningfully in the Ho Chi Minh era," he said.

Secondly, he is proud of his work relocating 192 severely wounded veterans from the Phuoc Binh veteran center back to community life in Ho Chi Minh City during the early 1980s when he led the Department of Labor, War Invalids and Social Affairs.

"After listening to the wounded veterans' wishes for better living conditions, I petitioned the city leadership to allow them to settle in vacant houses throughout the city," Cang recalled.

Despite some concerns that their presence might disrupt the city’s order, Cang argued passionately: "These veterans sacrificed everything for our nation. If they are given decent living conditions, they will have no reason to cause trouble."

With support from city leaders, including then Party official Phan Van Khai, within two years, Cang successfully relocated all 192 veterans - with no incidents reported afterward.

"This work brought me immense pride," Cang said, noting that military officials later praised the program for its success.

Memories that endure

Now in his nineties, Cang’s memory sometimes fades, but some events remain vivid.

One is the afternoon of May 18, 1968, during an air raid at Phuoc Van, Can Duoc District, where he narrowly survived a bombing that claimed the life of a young bodyguard, Ut Duc, who sacrificed himself to save him.

"I can never forget the sight of Ut Duc, who pulled me into a bunker and shielded me with his own body during the bombing," Cang said, voice trembling.

He also carries tender memories of his wife, whom he married over 60 years ago.

Shortly after their wedding, she was sent to Laos for several years. By the time she returned, Cang had already gone to the South.

"She wrote to me, saying, 'Whenever you have a place, call for me.' But the chance never came," he shared.

Last year, he visited her in Bac Ninh, and she tearfully said, "I thought you had forgotten me."

Such memories, both of love and sacrifice, remain treasured in Cang’s heart - reminders of a life lived with unwavering dedication.

Ngan Anh - Khanh Hoa