Thanh’s small house in Vinh Cuu district in Dong Nai province looks like a miniature museum. In his living room, visitors can see his portraits painted upside down on mirror, works painted on bottles or paintings depicting heroes and martyrs.

While flipping through the book “Sang ngoi chat ngoc anh hung” (Shine of Heroic Jade) about the Heroic Vietnamese Mothers of Dong Nai Province, Thanh introduced the portraits of the mothers that were reconstructed with 95-100 percent accuracy and confirmed to be authentic by relatives.

"Each photo contains a story, a memory that I evoke from limited sources of information or descriptions from people who knew the characters," he said.

For Thanh, painting heroes’ portraits is not just a passion but a way to express patriotism. It allows the departed to reappear, helping families reconnect with their past. To him, this is the most meaningful outcome.

Every stroke and color carries emotion, giving his works soul and touching many hearts. He hopes his paintings bridge history, helping younger generations understand their predecessors’ sacrifices.

“Some portraits make relatives weep, as if they can reunite with loved people after years apart. That’s my greatest motivation to continue,” Thanh said.

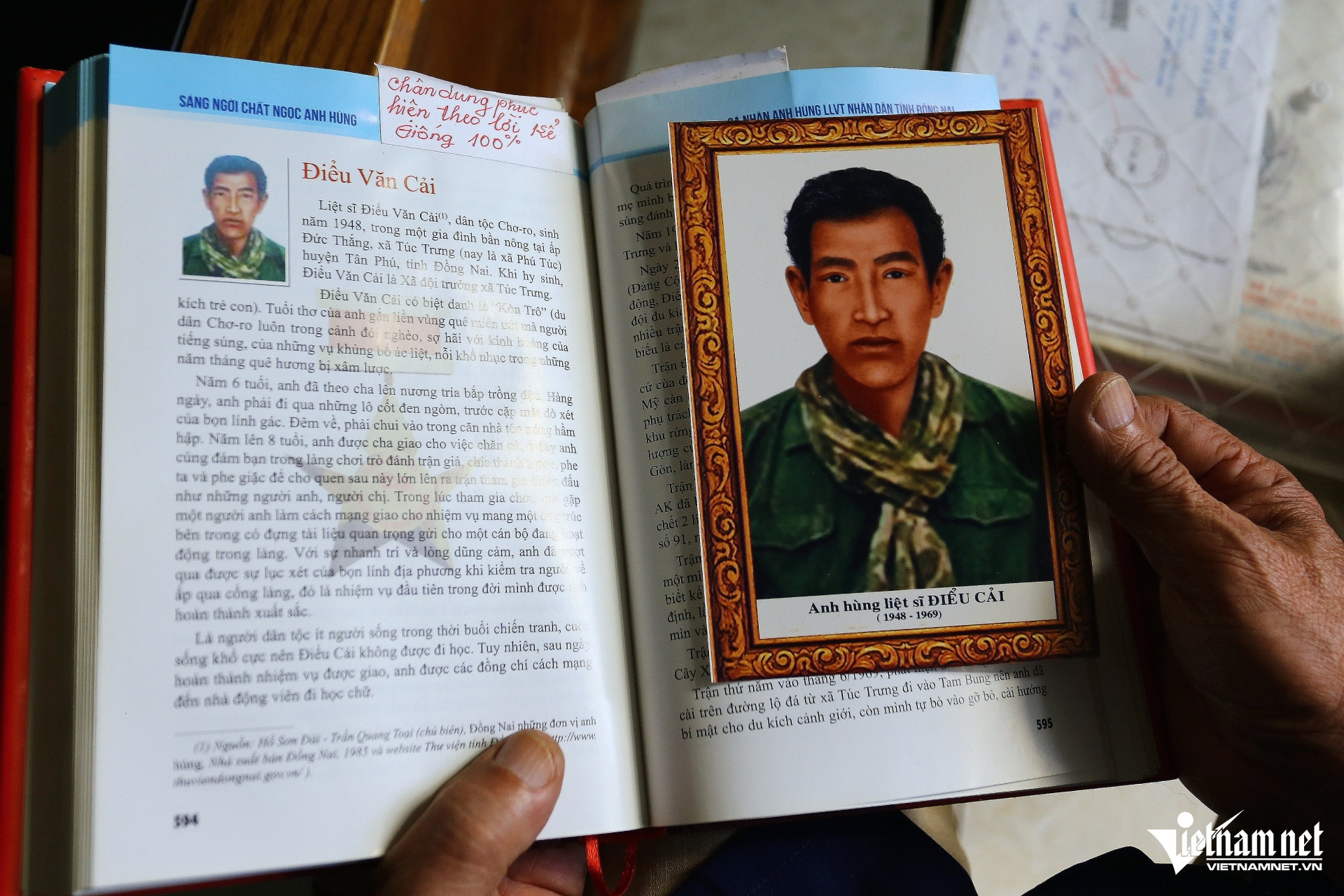

Among hundreds of works, the one that left the deepest mark is the portrait of People’s Armed Forces Hero and martyr Dieu Van Cai, also known as Dieu Cai (1949-1969), a Cho Ro native from TucT rung Commune, Dinh Quan District. He was a brave, resolute fighter devoted to national independence.

Dieu Cai is a symbol of the entire Cho Ro people. Yet, 45 years after his sacrifice, no photograph of him could be found locally.

Dinh Quan District’s Propaganda Board proposed reconstructing his portrait for educational purposes. Vo Tan Thanh was tasked with recreating the martyr’s image based on witnesses’ memories.

The reconstruction process was challenging, as Dieu Cai’s relatives were elderly with their memories fading. Local authorities sought out former comrades and acquaintances to gather details. Thanh traveled across Tuc Trung, meeting witnesses to record smallest fragments.

“No one remembered his full face. Elderly witnesses had foggy memories, but even a few details were invaluable. I synthesized, analyzed, and sketched multiple angles for recognition,” Thanh recalled.

With no reference photos, Thanh relied on oral descriptions. The most consistent detail was Dieu Cai’s long, curved, cleft chin. From this, Thanh drafted portraits from various angles, then created a frontal view for collective review.

After completing the draft, those who knew Dieu Cai were asked to give feedback. Thanh and witnesses refined the portrait over a month, ultimately selecting the version with 98 percent accuracy to his living image.

Hoang Anh